Eddie Redmayne’s Performance as Stephen Hawking Sparks Oscar Buzz in “The Theory of Everything”

In 1963, while attending the University of Cambridge, Stephen Hawking, a brilliant student, was diagnosed with ALS, a degenerative form of Motor Neurone Disease. He was given the earth-shattering news that he only had two years to live. The fact that Stephen Hawking, now 72, went on to not only write the bestselling avant-garde book, A Brief History of Time (an attempt to explain the universe in simple terms), but also to have a loving marriage that bore him three children is miraculous in and of itself. It would appear that this fairytale story deserves a fairytale ending, but alas, Stephen and Jane Hawking’s life together was filled with disapproving in-laws and extramarital affairs. The film doesn’t sugarcoat their struggles; we share their triumphs as well as their defeats.

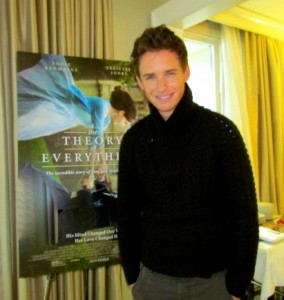

Eddie Redmayne, a British actor who is known for his roles in Les Misérables (2012) and My Week with Marilyn (2011) delivers a mesmerizing portrayal of Hawking in the film. If you haven’t seen either of those films, you just may recognize him from his stylish Burberry clothing advertisements.

Stephen Hawking’s story is based on source material from a memoir, Traveling to Infinity: My Life with Stephen, penned by his first wife, Jane Hawking. The film spans three decades and requires an extreme physical transformation by Redmayne, as in contorted body movements, unnatural facial expressions, and slurred speech. If you’ve seen Daniel Day-Lewis’s Academy Award winning performance in My Left Foot (1989) as Christy Brown, an Irish writer and painter who was born with cerebral palsy and could only write, type, or paint by use of the toes of one foot, then you’ll have an idea of the physical complexity of this role. And yes, Redmayne is creating mega Oscar buzz through a similar character adaptation.

Many questions are palpable after viewing the film. Having the opportunity to have them answered by Redmayne provides insights into the backstory of this extraordinary film’s production. We discussed his meeting Stephen Hawking along with the members of Hawking’s family, his preparation for the role, the physical demands required, Hawking’s keen sense of humor, co-star Felicity Jones’s incredible strength as Jane Hawking—which, by the way, he perceives as the backbone of the film – and the joy they experienced by improvising various scenes.

I caught up with Redmayne at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in Chicago and was thoroughly enlightened by the stories surrounding the foundation for his challenging role as Stephen Hawking.

Sarah Knight Adamson: Did you meet with Stephen Hawking and did he give you any advice?

Eddie Redmayne: Yes, I met him. I basically was so nervous that I ended up just telling Stephen Hawking about Stephen Hawking for the first twenty-five minutes. What did I learn from him? More than anything, he has this vivacious, playful, witty, deeply funny charisma that emanates from him, even though he can move few muscles now. That was the overriding thing I took away, but also, there were specific things. Like he asked me whether I was playing him before the voice machine. I said, “Yes.” He said, “Well, my voice was very slurred.” Aspects of the performance that he cared about specifically, he highlighted. That was important to me.

SKA: How wonderful. From reading the press notes, I know that Stephen allowed you to use his voice in the movie. How was that different from, say, Roger Ebert’s computer voice? I know Roger used a voice called “Alex” that’s from an Apple Mac. They sound a little similar to me, but I’m sure they’re not.

ER: Well, that is interesting. You know Stephen had a tracheotomy in 1985 – I think that was the date. After that, he had this voice made for him. At the time, it was very specific and the early technology for that. Of course, at any point, he could have changed that voice to something more updated, but he became identified with it. That became his personality. It was an American-accented voice. He says quite hilariously that Americans tend to think it sounds Swedish, and the Brits think it sounds American. It’s very interesting to me the idea that that becomes your identity in some ways. He’s held on to that point.

SKA: Is it called something special in particular?

ER: No. I think it’s just his voice, but when we made the film, we used our approximated version of that. It was only after seeing the film that he very kindly gave us permission to use his voice. For me, that was incredibly moving.

SKA: That’s great. What I loved about the movie besides your amazing performance was the fact that the main focus centered on relationships; Stephen and Jane’s relationship, their family, their children, and their extended families. Could you speak to that, please?

ER: When you meet Stephen in the film, he’s a very healthy, fun-loving, young man. It was at age twenty-one that he was diagnosed with ALS, and he was given only two years to live. Meeting him now, you realize that the illness is entirely secondary. He has no interest in his physical decline. He is someone that has always looked forward, lived passionately, and lived his life in every moment of his life to its fullest.

That was what our film was about. I mean, you see the physical decline, but when I spent all these months preparing, working on that side, so that when it came to actually doing the acting, it was just the human story, the emotional story. As you say, the family story and also there’s humor and the incredibly uplifting side of a family dealing with extraordinary obstacles, but superseding.

SKA: That’s just wonderful. How did you feel during the days in which Stephen was on set?

ER: Oh my God. The first day that Stephen came to the set, there was a big scene, which takes place at the May Ball, one of these huge balls they have in Cambridge every summer.

SKA: I love that scene, by the way; simply beautiful! (Both chuckling)

ER: It was at nighttime, and they had these fireworks all ready to go off. Stephen arrived at night with his nurses, and he was up-lit, almost spot-lit, by his computer screen. On cue, the fireworks went off, and it was one of the greatest entrances that I’ve ever seen. It was amazing. Jane and Jonathan, Jane’s second husband, were there that day as well. It felt like a huge celebration.

SKA: Thank you so much for that story. I just love that. I couldn’t help but equate those fireworks with the stars and the correlation with Stephen’s field of study.

ER: I think that James, our director, was looking for all those visual metaphors, those things.

SKA: Yes, exactly. That’s what I was trying to say: metaphors! Thank you.

ER: I think he was trying to find that idea of the intimate, of relationships and how profound they are in our lives. Also, the macro sense of small we are in the universe. He was using all the visual tools he could to express that.

SKA: That ball scene was just so beautifully filmed, as was the scene on the bridge. Can you talk about that?

ER: Yeah. It’s a scene at the end of the ball where they kiss for the first time. It’s on the bridge and Stephen’s refused to dance. He was a strong-willed young man and he had no interest in dancing, even though Jane wanted to dance. Eventually, throughout the evening, he eventually asks her to dance. What was important to me about ALS disease, people never know quite when it starts, when it manifests itself. Because, often, they’ll go into hospital after having fallen, without really realizing what caused it. I thought that probably from the beginning of the film, it was already in him, the ALS. Silly thing, but how we danced, I was hoping that I could show a little bit of that physicality just wavering slightly there in his hands and his feet.

SKA: It was beautifully done. You spoke a little bit about the humor in the film that I totally appreciated. It does come through loud and clear. Was some of that improvised?

ER: Yes. James Marsh, our director, was always encouraging us to improvise. Felicity and I are old friends, as is Charlie Cox, who plays Jonathan. Yeah, we messed around a lot. That felt in keeping with Stephen’s mischievous personality.

It was important because of the things I learned in the process, like meeting Stephen’s youngest son, Tim. He said to me, “We used to jump in Dad’s wheelchair and use it as a go-kart, or we would put swear words into the voice machine.” All of that freed us up and allowed us to make it more to be respectful to the illness, but also to be true in living with it in a fun way.

SKA: How great; it does lead to a more natural performance. I do want to ask you about one of my favorite lines in the film. Tell me if I’m not getting this right. When Jane says to you, “I love you,” and I believe that you say as Stephen, “That’s a false conclusion.”

ER: Yes. “You’ve leapt to a false conclusion,” I think the line is. It’s interesting because I didn’t know when I read that whether this was too stereotyped a portrayal of scientists as seeing very black and white and specifically, but it became clear. Meeting various people who had worked with Stephen or been students at Eaton [College], it could well be something that he would say. That’s quite a funny line. (Laughing)

SKA: It is. I just thought it was perfect with his apprehension in the first place.

ER: Yes.

SKA: He thought, “This is my last chance. I’m going to say this.” She wouldn’t take “no” for an answer, which I loved too.

ER: Yeah. I know. She’s so strong. Her strength and Felicity’s strength are the backbone of the film.

SKA: Sure. This is such a physically demanding role. I also know that you lost a lot of weight for this. What did you do to prepare?

ER: The problem, I suppose, that we came across was that we couldn’t film chronologically because, economically, it’s unviable now to make films that way. I basically spent four months going to an ALS clinic in London, working with a specialist there and meeting people who were suffering from this disease. Trying with a specialist by showing photos of Stephen as a young man because there’s no footage to see what his decline may have been. I then worked with a dancer-choreographer who helped find a way to place that in my body.

Then, it was about meeting Stephen’s students, trying to get my head around the science. As you say, losing the weight but working with the costume department and the makeup department so that I could look healthy to begin with, and then we could expose that weight loss through the different moments in the filming if we needed it. I really describe it as being an orchestra with James Marsh, our director, as our conductor. Everyone was working in concert with each other. It felt like a special one.

SKA: Speaking of costumes, I believe there were over 77 costume changes.

ER: Poor Stephen Noble, the costume designer. There was a huge amount of costume changes. Both Felicity and I were very meticulous. I remember when we went to have dinner with Jane Hawking and Jonathan and Timothy. It was at Jane’s house. I remember going into the house and finding Felicity in Jane’s wardrobe, looking at everything. Everyone cared very much about the costumes and getting that right and also as a way of expressing time changing.

SKA: Exactly. Because this film spans, I believe, twenty-five years.

ER: Exactly that. From the sixties into the eighties.

SKA: How wonderful. I guess I have one more question. What would you suppose or maybe what do you hope that viewers may take from this film?

ER: I suppose, for me, making the film, what I found astounding was this idea that Hawking was given two years to live at age twenty-one. With the help of Jane, he took that as a catalyst to live every single moment of his life as fully as possible and with great passion and with great joy. I’m someone that you get caught up in the foibles of your own life and the problems of this, that, and the other, constantly trying to remind yourself of when the stakes are that high, when every day, after those two years, he describes as being a gift in how you live your life fully. It’s incredibly admirable and something worth aspiring to.

Sarah Knight Adamson © November 8, 2014