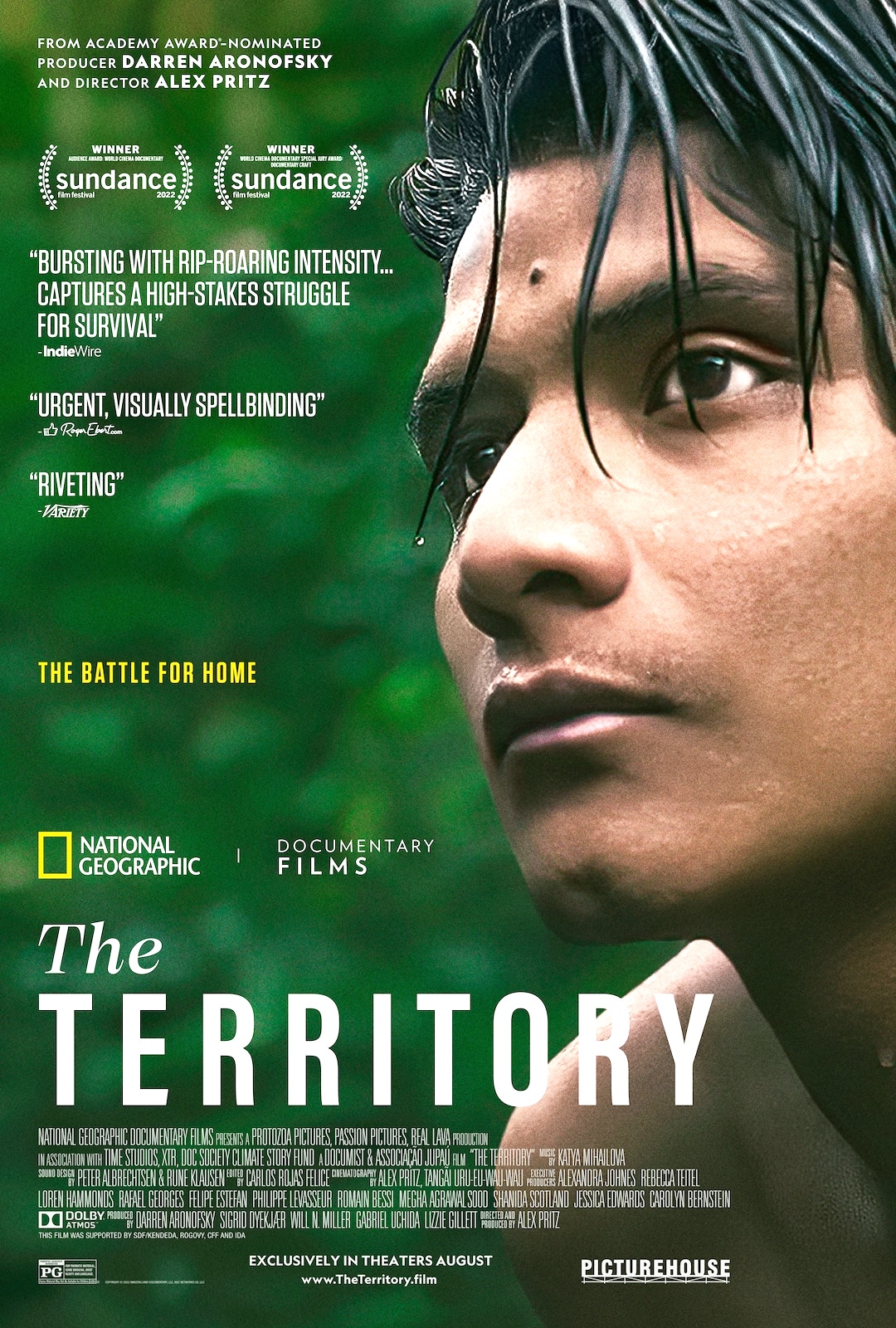

My interview with director Alex Pritz, the director of “The Territory,” an enlightening view of the Amazon Basin and deforestation issues, was via Zoom video on August 11, 2022. As a school teacher and curriculum writer in my former career, I wrote a unit of study for 14 schools to teach about Brazil’s Amazon Basin and my classroom.

The Amazon Basin Rainforest is a topic that I’m very familiar. Not only the natural beauty but also the continual problems of the burning, logging, cattle ranching, and farming of the Indigenous Uru-eu-wau-wau peoples’ land. It was indeed a full-circle moment speaking with director Alex Pritz and the people associated with the film to learn about the updates on the same problems my prior students studied.

Sarah Knight Adamson: How did you feel about the scenes that you let the tribe film?

Alex Pritz: To me, those were some of the most interesting scenes in the film. I had no idea what I might end up with. It was a total gamble at the time, but I think it was one of our best decisions.

SKA: Oh, fantastic. I feel like what it also did for you as a filmmaker, and the filming in general, is to give a more natural look. The people were not nervous or shy in front of a camera, as I have seen in the past. I was curious as to what year you started filming the indigenous people and what year you finished?

AP: We started in 2018 during the elections, then we filmed all the way up through late 2021 and finished the film in 2022; we had another small production trip in 2022, even after Sundance.

SKA: What were your most significant obstacles? And I’m sure there were many filming on location in the rainforest.

AP: There were so many. It’s a really difficult environment to film, and things are far apart; it takes six to eight hours to get between the different Eruwow villages. Smoke, fire, all of that. We lost a camera to the rain, just being out in the forest, one of our producers got malaria at one point, countless flat tires, and delays. Then just the general spectra of violence, which got brought home for all of us when Ari, a 33-year-old, one of the leaders of the tribe, was killed, yes, it was a difficult film to make.

SKA: Yes, heartwrenching. I know you’ve been asked this before, but I would like to hear it in your own words. How in the world were you able to gain the Indigenous population’s trust and say, ‘Hey, we’re going to come in here, and we’re going to film this?’ As you and I know, they’ve been mistreated and lied to in the past.

AP: Yes, and mostly at the hands of people who look like me and who come from similar places and behave culturally like me, and so it was a really long, slow process. I had to listen and talk about any of their fears and concerns, also sharing about myself, my motivations, and what I think the film is all about. The elders in this community hadn’t seen a feature film, which made it a difficult conversation. We had conversations about practicing and demonstrating making a film. We brought extra cameras and said, “You interview me, I’ll interview you.” Everybody points the camera at each other and makes it kind of fun and open, and also talks a little bit about editing and how much power there is in editing to sculpt and shape people’s perception of a group. There are ways that you can cut things that make a scene feel more dangerous.

There are also ways you can make a scene feel happier, and that’s a lot of power over somebody else’s narrative and a lot of trusts to place in somebody else to be a responsible sculptor of that narrative. So we felt like demonstrating that in a hands-on way was the best method we could find to open up that discussion and its most honest form.

The elders speak a language called Kawahib, that’s part of the Tupi-Guarani family. It’s spoken by something in the low thousands of people left on Earth, so there’s a whole language culture. That was a divide between myself and them.

SKA: I can’t even imagine it must have been so exciting when it started.

AP: Yes, it’s exciting now, too; we’re really looking forward to this impact campaign that we’re building around the film; we’re helping build a multimedia cultural center within lever Tory, where they’ll have an area to screen their own films, podcasting studio, production studio, editing stations to be able to use.

SKA: I wanted to let you know that I have interviewed the documentary filmmaker Alex Gibney. I don’t know if you know of him. If so, I was wondering what you’ve learned from him.

AP: Oh Yes, I know him. Alex is a titan of the industry. I think his work speaks for itself. He is a consummate documentarian interested in truth in a very deep way. He’s also really supportive of younger filmmakers in an exciting way and giving back to the industry. Yeah, he was an executive producer on a film I shot last year called “The First Wave; I have a lot of respect for him.

SKA: So your film for me, and I would imagine for most people, it’s so visually beautiful. You’ve captured the leaf cutter ants and those tree frogs and brought it back from me, but you also brought the burning back. It is incredible to capture the scenes of the actual burning by the people doing it. I can’t even imagine, but they didn’t mind, and how did you get permission to film them?

AP: They see themselves as the heroes. They see themselves as the pioneers who are going out and creating something out of nothing, turning wilderness into private property, and what could be more virtuous than that? They know that what they’re doing is illegal and that it’s frowned upon by the international community. I showed them the scenes that involved themselves, and they said, “Great, you nailed it, like go tell the world about our story and how persecuted we are. They see themselves as the victims of this unfair criminalization of their lifestyle. That’s how they view themselves.

Also, I think the chain saws at the beginning of the film, we really try to pay a lot of attention to sound design and really make sure that that you could hear and feel the rain forest and its beauty and its majesty when you’re out in it, but then also the kind of terror that comes from its destruction.

SKA: Oh, absolutely, no, you’ve done a fabulous job. In your travels around the world. What have you learned about people?

AP: I haven’t gotten that question before. I think we’re more similar than we are different, on the whole. In many places, there’s a political class, and economic and cultural elite can create conflict between groups of people that wouldn’t otherwise exist. I look at Brazil and the forces that are holding these farmers back. These poor, marginalized farmers are the same forces that are plundering indigenous land. They’re victims of the same types of forces. Still, the political class in Brazil has pitted these poor farmers against indigenous people, feeding them this false idea that Indigenous people have too much land and others are holding them back. Look at the land distribution between these wealthy mega rangers, these posadas, and these poor, marginalized landless farmers, let’s think about wealth and equality in that direction, and suddenly the conflict can start to feel very different.

SKA: Exactly, and the other point I’ve tried to drive home with my studies of the rain forest, what the burning does to nature, the animals and the insects and the life. I taught about the spider monkey that needs 2,000 acres or 800 hectors to survive in the wild. And what about the species that will not be discovered because their home is destroyed?

AP: I think they discover a new species in the Amazon rain forest every two days, and that’s without looking very hard; you can just imagine how much else is out there. It’s such a beautiful ecosystem. I think the more we learn about trees, especially really old-growth of trees. How they communicate and how they need other big trees around them, they can’t exist in isolation, and when you start to fracture the forest too much, it begins to disintegrate. Yeah, all of these are connected and we’re reaching a dangerous tipping point with the rainforest where the more than 22, 23% of it is cut down, were likely to enter a new cycle of desertification, where the rainforest itself moves from being a carbon sink to a carbon source and starts to become a savanna that’s horrible for the global climate right now, we’re at 18% of the rainforest haven’t been cut down, so we’re right at the knife edge with this thing and we can’t afford to… Any more time?

SKA: Exactly. I want to thank you so much for all the work you’ve done and all the hardships you’ve gone through with this film; I know it was very challenging, but you are spreading the word of a very serious problem for our whole world, and the world should all embrace this timely film.

AP: This affects all of us. This is not an issue that only Brazilians should be concerned about. This is any one of us who has kids or elderly loved ones who could be affected by heat waves. Yeah, concerns as all.